Juneteenth Pride: Honoring Willi Smith, The Visionary Designer History Erased. Until Now

Time has a cruel way of dusting its hourglass sand over monuments. If that can be said for the newly discovered world wonders, the same can be said for those who have built their own monuments within culture. Willi Smith’s story today screams to be uncovered perhaps more than any other. Especially today.

Before there was a Virgil Abloh, Telfar, & Pyer Moss- there was Willi Smith. And none of them would exist if he didn’t first. Full fucking stop.

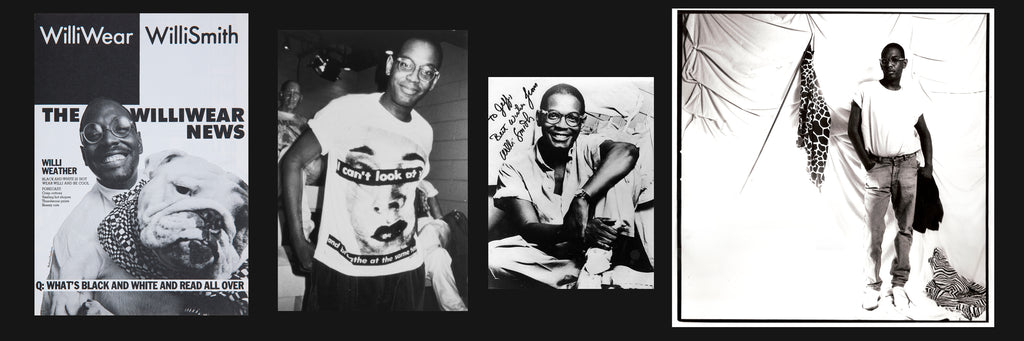

At one point, Willi Smith was regarded as the biggest Black designer on earth. He founded WilliWear Limited in 1976 and within a decade he grossed over $25 million in sales. He died in 1987, and WilliWear sadly folded in 1990, with the industry all but forgetting the icon.

WilliWear was the first clothing company to create womenswear and menswear under the same label. The accessibility and affordability of Smith's clothing helped to democratize fashion. Everything he did, he did with the unapologetic passion and creativity that only comes from the freedom of being a social outlier.

Smith was gay & Black - two strikes against you before you even stand in an on-deck circle in the 70’s. He was a force of nature, a rarity in the era when huge, upmarket fast-fashion designers like Ralph & Calvin defined what the American look was. To say that Smith was a fallen star would be unfair. He was a star, despite all the odds stacked against him by birth, and he built an empire. To compare him to other fallen empires outside of fashion is not unfair however, but it would have to be noted his empire shared more in common with the Etruscan than Roman. History heralds the Romans. We forget that the brilliant Etruscans were the giant shoulders the proverbial (and literal) Caesars stood on.

I digress.

Born in 1948 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Smith often joked that his mother kept “more clothes in the house than food.” This birthed a wild passion for both art and design in equal doses. His youth was spent sketching in notebooks his parents couldn't keep in stock. As he became a bit older, he swapped his home floor for the floor of the Philadelphia Museum College of Art.

Smith was very close to the family’s matriarch, his grandmother. In the late 60’s and early 70’s, the aging maid inadvertently started Willi’s fashion career. One of the homes she cleaned was that of a friend of Arnold Scaasi, the Canadian luxury designer who outfitted Liz Taylor. She used that connection to plug young Smith into his first internship.

He began taking night courses in downtown Philly for fashion illustration. He then moved to Manhattan when he received two scholarships from Parsons -the art and design wing of the iconic NYC creative college The New School. In 1965, Smith interned for the very same couturier Scaasi, whom his grandmother knew from her days as a maid for one of his friends- and began studying fashion design at Parsons in the fall while balancing liberal arts classes at NYU. He was expelled from Parsons for an alleged gay relationship with another male student. It didn’t really even phase him.

The man just didn’t fucking stop. He was only beholden to the vision.

His hard work paid off, as he became one of the faces of an emerging subculture wave of young Black American designers & pop artists who kickstarted their street born trajectory in the 70’s. The look was mold breaking and daring, the art was loud & took elements from train car graffiti & the soundtrack was this new shit the kids were playing in the parks called hip-hop.

On the fashion side, there was Patrick Kelly, who found fame in France with his controversial designs, and celebrity darling Stephen Burrows. There was also Jax Jaxon (“the first black designer to be at the helm of a couture house: Jean-Louis Scherrer from 1969-1970,”), and Smith’s best friend Alvin Bell.

In the early 70’s, Smith worked as lead designer for the now defunct, upstart juniors sportswear label Digits. Smith met future business partner and lifelong friend Laurie Mallet in 1970 while Mallet was in New York for a holiday break and hired her as his design assistant at Digits in 1971.

The following year, 1972, Smith was nominated for the Coty American Fashion Critics’ Award for his work as lead designer at Digits. He quickly began designing patterns for the commercial pattern company Butterick. Smith resigned from Digits later that same year and Digits went bankrupt shortly after. In 1974, Smith partnered with his sister Toukie Smith and close friend Harrison Rivera-Terreaux to form his own label Willi Smith Designs, Inc. By 1978 Willi Smith Designs was a bust, they were out of money and hadn’t sold much. Factor in begging gay, and Black, and the future of Smith’s vision was all but aborted.

In 1977, Smith needed inspiration. He continued to toil through the funk, spending his nights in Manhattan bars, drinking in the chaos of Warhol’s New York, surrounded by poets, painters, gangsters & junkies. On Mallet’s advice, he traveled to Bombay India with Mallet to produce a small collection of women's separates in natural fibers. He had heard through the grapevine India’s “natural fibers” would be a revolution in fashion, and Mallet had a plan. The gods finally smiled upon Smith.

The collection was a hit, and soon after, Smith and Mallet formed the label WilliWear Ltd., with Mallet as President of the company and Willi Smith serving as ceremonial Vice President and lead designer. The real ones knew he was the whole show. Titles are for those who do nothing. The first Williwear fashion show was held at the Holly Solomon Gallery in the Spring of 1978 and showcased a collection of garments “influenced by nautical uniforms and Southeast Asian dress.”

Subsequent WilliWear fashion shows were held in unconventional locations for traditional runway experiences and focused on authentic Black community energy. Alvin Ailey’s Studio and the Puck Building in Nolita were two of Smith’s very calculated venue choices.

He finally arrived.

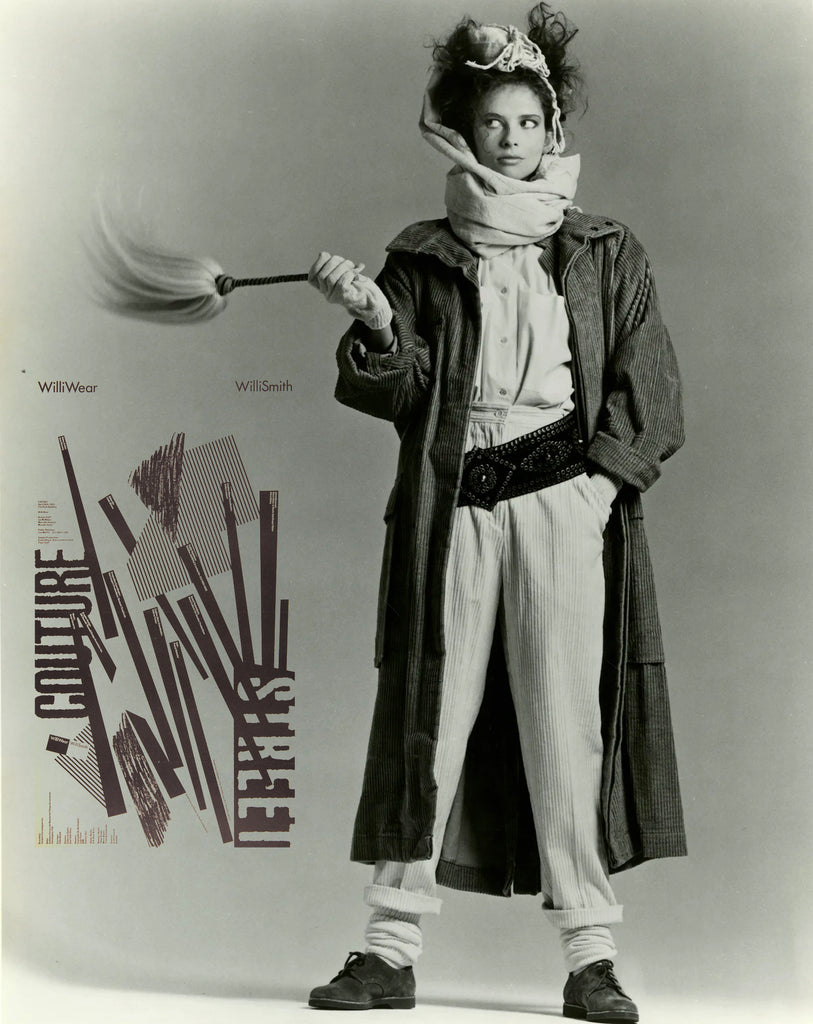

Williwear hit its stride in the early 80’s when the label incorporated core elements of hip hop culture into its aesthetic, most notably his 1983 autumn-winter collection called “Street Couture” - which featured urban music and dance performances. That year Smith became the youngest-ever winner of the American Fashion Critics’ Award for Women’s Fashion.

His work was far ahead of its time: mixing the relaxed fit of sportswear with high-end elements of European tailoring. His clothes reflected his innate worldview- inclusivity & accessibility with style. They were not meant to be untouchable, high street Monaco galleria wear.

While the term “streetwear” has been lately either pejorative or meaningless since 2017, Smith’s more fluid understanding of the term (“bringing urban culture to the catwalk”) has been incredibly influential.

“He mixed looks from workwear, the military, African and Indian prints,” says fashion historian Darnell-Jamal Lisby. “He was enamoured with denim and the idea of the romanticised Americana & Wild West cowboy, often incorporating tweeds, denim or corduroy into his collection. He loved jumpsuits and the utilitarian aspects of the silhouette.”

He was also fearlessly hip-hop & pop art, a contemporary to Basquiat & Haring in his luminary status amongst the NYC cool kids circles. He bridged the gap between the curator, buyer & LES junkbox in ways that one couldn’t even connect for decades. The current landscape has made a meal out of that juxtaposition. Smith did it first.

“Fashion is a people thing and designers should remember that. Models pose in clothes. People live in them.” Though he was inspired by New York City, he wanted people everywhere to appreciate the culture and inspiration of the city. “Being Black has a lot to do with my being a good designer,” Smith said. “Most of these designers who have to run to Paris for colour and fabric combinations should go to church on Sunday in Harlem. It’s all right there.”

“He was a huge hero to African American women,” says Kim Hastreiter, the founder & former Editor-In-Chief of PAPER Magazine who was a personal friend of Smith in the 80’s. “They worshipped Willi and felt such enormous pride in his success. He was a black man who could change our society’s inherent racist perception of black men in general,” she says. “[For black women he became] their dream husband, dream boss, dream best friend, dream leader, their dream son, dream teacher. He represented so many dreams, their dreams for the future of their African American community. A lot was projected onto Smith. It must have been a lot of pressure.”

“He loved street culture and made clothes for people to wear on the street.” Hastreiter continued.

Smith's gender-neutral collections for WilliWear can be seen as precursors for contemporary gender-neutral brands such as One DNA and the Phluid Project. Smith's influence can also be seen in brands such as Supreme, Off-White, Telfar, Vaquera, Eckhaus Latta and Pyer Moss.

WillieWear became a fashion zeitgeist, a way-ahead-of-its-time bottle of lightning, doing 25 million in sales at its zenith. Smith, the man behind it, always seemed in awe of it. He got a childish joy out of seeing his pieces in the NYC streets.

“We’d be walking along and he’d say, ‘Oh my God! That person is wearing my jacket,’ ” recalls James Wines, the founder and president of SITE. For Smith, the woman in the street was both his inspiration and his intended audience. “Willi once said that he didn’t do clothes for the queen,” said Laurie Mallet, his partner since the inception.

The founder of “streetwear” was also the founder of the “collab.” In a host of ways, one can not exist without the other, as street culture is participatory & bottom up by nature, reversing the flow of the institution at its very core. He began teaming up with Pop Art creatives, rappers, models & musicians of all genres to expand the narrative & footprint of the culture that began in his head.

He commissioned multi-disciplinary visual futurists Nam June Paik and Juan Downey to create video installations & “moving picture sets” for his runway shows. He collabed with Keith Haring and other artist friends on capsule collections of T-shirts; and created art of them - a grid of flat, white plaster “clothes” for a show at MoMA PS1.

“He knew and worked with everybody in that sort of post-pop landscape,” James Wines, founder of art & architecture icon SITE says in retrospect. “And he had this really collaborative spirit, which at that time was really unheard of. Now everybody is trying to do it.”

“I don’t believe my creativity is threatened by commercialism,” Willi told Fashion World in an interview. “Honestly, quite the opposite—I think that the more commercial I become, the more creative I can be, because I am reaching more people.”

The accessibility & entry point of WilliWear was its magic. It was more about “cool” and less about the price point. Smith’s designs suited a wide variety of body types, races, lifestyles and aesthetics. It embodied a bygone era- Manhattan in the 80’s.

“It’s entirely possible that he could have had a brand as big as some of the really big American household names that we have now. But of course we will never know.”- James Wines, founder, SITE.

In 1987, Smith wanted to return to his inspiration roots, India. He loved India for all it gave him, the original energy that would become his line & legacy. In a tragic turn of events, he went to India as a personal pilgrimage of reflection and contracted an infection and pneumonia that would end his life.

He died upon returning home at Mount Sinai Hospital in April 1987. Tests later revealed that—unbeknownst to even his closest friends—he had in fact, contracted AIDS. Whether he was unaware of his status or simply in deep denial remains a mystery.

He was only 39.

WilliWear unraveled quickly after in just 3 short years. It was said that Mallet was never truly the same after he was gone. She made a ballsy attempt to keep the business going, discovering the young, talented designer Andre Walker to take the lead and even opening new boutiques. All attempts failed.

The magic had gone to the grave with the magician.

WilliWear folded in 1990, and the fashion world did what the fashion world always does. It moved on to the next shiny object & hot trend. Fuck you, fashion. Just fuck you.

New York City has a really short memory. It’s even shorter for its native sons & daughters who are designers, entertainers, or athletes. The fact Smith died of AIDS in '87, when the mere mention of the disease was enough to start a press panic, was really a crushing blow to his legacy. Blaming & shaming the gay community was another quiver in the bow of Manhattan’s cultural Alzheimers. No one wanted to discuss, let alone applaud, the legacy Smith left behind.

On to the next shit, there's always another subway train to catch in NYC.

“Fashion history, for the most part, has been white history. The heritage of the European luxury houses dominate the history of what people believe fashion to be. On the whole, we have designers of color missing from the textbooks.” Said Parson’s Fashion Historian Kim Jenkins.

We didn’t want to forget him. There would be no us without Smith. There would be no Pyer Moss, Telfar, Virgil Abloh or Jerry Lorenzo if Smith didn’t at least pave the way, opening minds to what dreams may come.

Today, on Juneteenth & Pride Month, we honor the legend. Do your homework on him. Research his work. There’s a lot of work to research. Know the history. Find yourself in Smith, carry that torch in whatever way that looks like to you.

You can’t know where you’re going until you know where you’re from. We’re all from Willi Smith, whether we know it or not.